BFF FILM & FESTIVAL BLOG

The Last Out: Q&A with Directors Sami Khan and Michael Gassert

Written by Aubrey Benmark

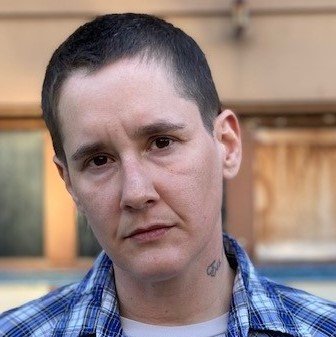

Carlos González in The Last Out Photo Credit: Sami Khan and Michael Gassert

October means one thing to die-hard baseball fans— Major League Baseball playoff season. Millions across the nation collectively hold their breath at every pitch as the best teams battle their way towards the World Series, but for Cuban athletes it takes significantly more than talent and training to bring them to the pinnacle of their profession. Due to a decades long trade embargo between the U.S. and Cuba, most Cuban ballplayers must face perilous travel conditions via human smugglers as they defect from their country knowing they might never see their families again, risking exile if they succeed, and all before they reach a foreign training camp where they are required to obtain residency, or no MLB club can even consider them.

The Last Out, a feature-length documentary directed by Oscar nominated Sami Khan and Michael Gassert, details the journey of three players, Happy Oliveros, Carlos González, and Victor Baró, as they struggle to make their greatest dreams a reality. Filmed over a four-year time span, Khan and Gassert dedicated themselves to an honest and emotional depiction of the nefarious Cuban pro baseball pipeline. At times the story is heavyhearted, the disappointment and homesickness from Oliveros, González, and Baró is palpable, but the camaraderie and love they offer each other uplifts the soul. Despite devastating setbacks, the men forge ahead to build better lives for themselves and their families. I’m fortunate to ask the directors of The Last Out, Sami Khan and Michael Gassert, a few questions about the inspiration behind this story and the process of making it.

As baseball fans yourselves, why was it important to you to capture this particular story, and did you know it would resonate with a much wider audience?

Sami Khan: Early on in the pandemic, there was nearly a collective “eureka!” moment for Western civilization. We briefly got a window into all the invisible people our fragile economy depends upon. Not just the nurses and doctors but the janitors, the truck drivers, the grocery store employees, the farm workers, and factory workers - they’re all threaded together in this delicate tapestry that modern life depends upon. In March 2020 when things screeched to a halt, we got a glimpse at that tapestry. Sadly, that moment has since been lost and we’ve moved on with our absurd existence of abundance and convenience. But, for us, about seven years ago, we started to think about that secret tapestry in baseball, specifically around the wave of dangerous defections from Cuba and the hidden cost, financially and morally, of the national pastime.

Michael Gassert: When Sami first pitched me this idea I immediately felt that dream you have as a little kid to reach the major leagues and come through for your team in the biggest moments. Any kid who’s thrown or hit a ball has also chanted; bottom of the 9th, two outs, bases loaded… But more than just chasing a dream with prospects in real time, I knew that Sami had keyed into something much bigger. That the inequities created by the US trade embargo on Cuba could lead us to some dark places as the demand for Cuban ballplayers was at an all time high. We soon discovered that by telling that story in a very intimate, personal way, we can open a portal to some bigger questions about immigration, the commodification of athletes of color, and the cost of the American Dream.

The migrant trail into the U.S. is often associated with manual laborers, not professional athletes, and yet the audience is afforded an up-close view of Happy Oliveros’s passage after he is surreptitiously cut from the training camp in Costa Rica. Was there a point in the journey when you feared that Oliveros wouldn’t make it into the United States?

MG: Happy’s journey and the process of making this documentary overlap in many areas but perhaps most comprehensively in their inherent uncertainty. There have been many twists and turns along the way, some foreseeable and others not. But like Happy, I think we always just tried to put ourselves in position to be successful and never give up. Palante siempre, candela!

There were certain moments along the way where Happy’s original plan didn't pan out and the odds were against him, but he found a way. For example, in a moment that you don't see in the film at the first border crossing into Nicaragua, Chele and I saw Happy being escorted by a border agent back into Nicaragua after we originally split off. I thought we might not reunite for a long while. But Happy met us on the other side with a 30 day visa no less.

But as the situation in Costa Rica worsened and the political situation changed under our feet, our concern grew for all the guys and all immigrants, in fact, who face such precarious circumstances. When Carlos tried to cross into Nicaragua a few weeks later, he had a much harder time, was stripped of all his money, and was fortunate to make it back to San José in one piece to try again the following month.

Official Movie Poster The Last Out

The inclusion of the athletes’ families back home in Cuba was especially touching to see in the film, as all of the men made enormous sacrifices with the intentions of supporting their loved ones. How was it for you to spend time with the families, knowing their sons could not go home and do the same?

MG: This was perhaps one of the most touching experiences for us as filmmakers. You feel so much for these guys not being able to just turn around and visit their families whom they love so much while they’re out there risking everything for them. Sami and I went on an epic adventure not just to meet up with a few relatives but track down and spend meaningful time with the immediate family members of all the guys, even those you don't see featured in the story. We felt it was vital in telling their story to have a strong, first hand sense of what they mean to their loved ones. Spending time in the players’ houses, eating their favorite meals cooked by mom all brought us closer to them and how meaningful of a sacrifice they each made. There were pig roasts in Mayari, river bathing in Baracoa, stories of achievement and longing everywhere we went. Being able to bring those photos, videos, personal notes and first hand accounts to the guys meant so much to them but also deepened the trust we had built. It also made more clear to them what we were really after in following their stories. I remember walking back to the barber shop with Baró after the emotional moment when he watches the video message from his mom at the stadium and he just turns to me and says, “I get it now Mike. I get it mi hermano.”

Near the beginning, your film highlights a troublesome statistic, “In the last five years hundreds of baseball players have left Cuba. Only six have made it to the Majors.” Initially over two dozen eager baseball scouts visited the training camp to assess Oliveros, González, Baró, and the other players’ skills, only for their contract negotiations to dwindle after months of not being able to obtain Costa Rican residency. While the odds of making it into any professional sports league are staggering, in your opinion how much of the austerity of their situation affected the players’ performance on the field as time wore on?

SK: We definitely saw the toll wear on the guys. One of the hardest things for all of them was seeing guys they used to play against sign multi-million dollar deals while they were waiting for their paperwork to clear. I vividly remember one instance where Mike and I rushed to tell the guys that one Cuban player they knew had just signed a huge contract and Happy said something like “That’s good for us. We’re at that same level.” But the contracts never came. A large part of that was because of mistakes Gus and his team made in the paperwork, another huge part was that the market shifted against the guys, and the final part was the emotional and physical toll it took on the guys which led to declining performance. But can you really fault someone for having one bad showcase when they’ve risked everything, left their homeland and their family and aren’t sure if they can trust the process anymore?

In previous interviews, you’ve discussed the cost that making it to the pros exacts upon the players, and that we are living in a time where athletes are heeding the call to social justice. As a devoted baseball fan myself, is there anything that fans can do, beyond raising their awareness of such issues, in order to support the current and future Cuban ballplayers trying to make it to the U.S.?

SK: In all honesty, fans should start to develop a sense of outrage that extends beyond just whining over a slugger popping pills or a team stealing signs. There are very shady things that go on in professional sports where young athletes are exploited by the system and too often fans have the attitude: “Oh, well if my team wins, I don’t really care.” That’s a messed up way to live your life.

One concrete thing right now fans can do is support Minor League players who are fighting for a living wage. There are ballplayers, Cuban, Dominican, and American who are making starvation wages in the Minors. Organize your buddies to write emails to your team’s leadership to ask that they pay their Minor Leaguers humanely. That would be a good start.

Directors: Sami Khan & Michael Gassert

Running Time: 84 minutes

Available to view Oct 20-24 at watch.bushwickfilmfestival.com

"Cracked": Q&A With Writer/Director Lin Que Ayoung

Written by Marisa Bianco

Meliki Hurd (left) and Tatum Marilyn Hall (right) in “Cracked” Photo Credit: Lin Que Ayoung

The narrative short category at this year’s Bushwick Film Festival is perhaps one of the most exciting. The films selected explore a diversity of experiences, defying genre and encompassing a full spectrum of emotions. One of my favorites is “Cracked”, an intimate coming of age story directed by Lin Que Ayoung. “Cracked” is Lin Que’s thesis project for NYU Graduate Film. Before her filmmaking career, Lin Que was a hip hop performer and lyricist. A musical sensibility clearly permeates her film work.

“Cracked” tells the story of Toya, a young teen in 1980s Queens, who fights with her siblings and navigates her first love. Meanwhile, she is forced to confront a past trauma. In just 14 minutes, the film touches on a multitude of relationships and themes, and it paints a full picture of Toya’s interior and exterior worlds. The film, in part funded by the Spike Lee Production Fund Grant, has had a successful festival run. It premiered at the Tribeca Film Festival and will now screen at BFF.

“Cracked” is one of the most arresting and emotionally gripping selections in the Narrative Short category at this year’s festival. I jumped at the opportunity to connect with my fellow NYU alum Lin Que Ayoung and learn more about this project. Read our conversation below.

Like you, I graduated from NYU virtually in May 2020. What was it like ending your time at Tisch online? Does the success of your thesis project, “Cracked”, in any way feel like a make-up graduation?

Graduating from NYU Grad Film marked the ending of a major journey in my life so graduating virtually had its pros and cons. After being in my thesis years, which included two years out of classes, I was looking forward to seeing my Tisch Family and having the opportunity to celebrate years of hard work together. It was difficult not having that opportunity, but we were able to still connect virtually and every last one of us was able to say something about their time at Tisch. This made it very special.

The success of “Cracked” is a joint venture and something that highlights the importance of all the incredible relationships I've been able to make at Tisch, the collaborators I plan on working with throughout my career. It's been absolutely a Blessing celebrating together as fellow filmmakers and filmgoers feel connected to the film.

This film clearly demonstrates an incredible attention to detail from you and your team, especially production design and wardrobe. I loved the way you give the viewer small glimpses into Toya’s world through close up-shots. It's the details in her home, the color of those details, and how they’re lit, that show us what Toya, her family, and Pooch are like. What details in the costumes, props, or production design were especially important to you?

Everything is/was important to me. I was born a detail-oriented person. The details are the underpinning that solidifies every other dimension of the film. It bolsters it up and hopefully imperceptibly draws the viewers into the world. It's absolutely delightful to know that you and others are noticing the decision-making that has been implemented to create authenticity.

Official Movie Poster for “Cracked”

Looking at your work on “Cracked”, where do you see the influence of your hip hop and music experience?

Music is so important to our culture. Within a millisecond, it can catapult us into a time and space with the efficiency of a state-of-the-art time machine. Its influence is so far-reaching. I had to work on post-production during Covid and I wasn't able to get the music that I wanted so I made the hard decision to record something myself, which in hindsight, made it even more authentic for me... being that “Cracked” is based on my childhood experiences. Prior to this, I would have undoubtedly told you that I was done rhyming. Life is funny.

You are open about the fact that “Cracked” is in part autobiographical. Did you always want to make a project using your own story? Or was it something that took time for you to become comfortable with? Has transitioning mediums from music to film changed your perspective on being vulnerable in your creativity?

Since I'm a former hip hop recording artist and lyricist, speaking from the heart is first nature and actually vital in order to connect with your audience. My aim as a filmmaker is to do the same. Film & television were Everything when I was a child. It showed me that there was a whole different world outside of my home, my block, my neighborhood. It fueled my imagination… and continues to do so every day. For me, my art, whether musical or visual, is about vulnerability. To me, my job as an artist is to have the courage to be vulnerable.

The ending of this film is incredibly impactful. During my first watch, I wasn’t sure how Toya’s father would react to what she told him. When his initial anger turns to love, and he embraces Toya, it feels right—because your film is full of love and warmth despite the trauma it addresses. What do you think this ending says about the relationship between anger and love, especially love that perseveres through trauma?

I probably get the most angry with the people in my life that I love the most. As a woman, I believe it is important to own our anger. As a society, I believe we are learning more about how to process anger in a healthy way. For me, emotions are signposts that help me navigate my inner life. It can get really tricky when I have mixed feelings. Anger and love can feel like they're on two opposite sides of the spectrum, but when someone loves you, they give you the space to process your anger. Anger can motivate you into positive action. Toya's father's anger quickly dissipates after he realizes what Toya needs at the moment. She needs unconditional love and that is exactly what he gives her.

Director: Lin Que Ayoung

Running Time: 16 minutes

Available to view from Oct 20-24 at watch.bushwickfilmfestival.com

Everything in the End: Q&A With Writer/Director Mylissa Fitzsimmons

Written by Kennedy McCutchen

Hugo de Sousa as Paulo in Everything in The End Photo Credit: Hello Charles LLC, Bearly There Media

Imagine Richard Linklater’s Boyhood and Eric Rohmer’s Le Rayon Vert creating an apocalyptic, grief-inducing film of silent self-exploration. That is precisely what Mylissa Fitzsimmons has created in her first debut feature film submitted to this year’s Bushwick Film Festival. A self-proclaimed fan of the slow-burn, or in Fitzsimmons words, “the quiet film,” the Los Angeles-based writer, director, producer, and photographer achieves her own version of man-meets-nature-meets-end-of-the-world. Viewers follow Paulo as he travels to Iceland, where he contemplates his tainted past, his sequestered present, and his unattainable future. We were able to speak with Mylissa about the genesis of her film, cultivating resourcefulness for low-budget indies, and her cinemagraphic inspirations.

Congratulations on your debut feature film! Perhaps the equally simplest and most exciting question: Why this film? What was the genesis of Everything in the End? What was its gestation period?

Thank you, and thanks Bushwick Film Festival for programming the film, we’re very excited to screen there. It’s been a great, but challenging adventure bringing my debut future to festivals this last year. The pandemic has made this film and the whole experience making it feel so much more personal.

In October of 2018, I was in Iceland as part of The RIFF Talent Lab, and the whole time there I just became obsessed with the idea of shooting a film there. When I came back to LA at the start of 2019, all I knew was I wanted to shoot a film there but had no idea what, when, how. I then was asked by Raul, a friend from Spain who I had met at the lab, if I was interested in doing a short film as part of a series of shorts about the last night on earth. Nothing came from that project, but that simple question of, “What would you do if it were the last night on Earth? “ really planted the seed for the idea of a film. I have always been a fan of dystopian genre films and kinda ran with the idea that I wanted to do this “end of world” film but actually not make a film about the end of the world. More so, I wanted to make a film about the kindness of people at the end of the world, so instead I gravitated to a story that was less plot driven and more emotionally driven. I really enjoy films that make me feel wrecked and depressed when I leave the theater.

I needed to do a feature film, I wanted to move forward with my film career and I just couldn’t do any more short films. By August 2019, we had finished crowdfunding, found two investors who put in some extra money to get us through filming it, and by September we had a cast and another draft of the script. We had a 5 person crew shooting the film, 2 producers, and a 10 day shoot schedule. Basically we somehow wrote, produced, and shot a film in 3 months start to finish.

Near the end of the film, Paulo asks his friend if he is going to church. His friend replies: “No. No, it’s too late for that. No, I’m going up that mountain.” This, to me, is an imperative motif of the film: a rejection of orthodoxy, particular orthodox forms of comfort and security, and an undertaking of the difficult, the uncomfortable, of nature in all its grim, sublime beauty. In many ways, perhaps, it is Sisyphus himself returning to the bottom of the hill to push the boulder up again. As the writer, what does this “mountain” mean to you? What universal human mountains, like death, is the film forcing to the foreground?

That mountain represents very different answers to those two characters who climb it. When writing I felt that this mountain was the final symbol of love, a place where one returns often because he fell in love there. A place where someone was conceived out of love, and finally a place where in the simple act of going to this place a person is fulfilling the last wish of a loved one and in doing so can finally forgive and love himself. There’s the line in an earlier scene where Ana says, “Death reunites us with the ones we love” -- to me death is the obstacle to that love, and the mountain is where one is reunited with the love, figuratively and metaphorically. In order to get to that place Paulo has to go through the process of grief; it’s messy, uncomfortable, and emotional. The beautiful thing he discovers about it, is that he doesn't have to grieve alone.

Official Movie Poster provided by Hello Charles LLC, Bearly There Media

What was the process like of capturing such an intimate audio-visual experience of nature, particularly in relation to such a natural phenomenon like death? How important was the location - Iceland - to your work, and how did you make your scouting decisions?

Financially, as an indie filmmaker who is also a producer on a micro budget film, Iceland probably wasn't the smartest decision. But as a director who started out as a photographer, visually Iceland was my only choice. From the very beginning, I knew that it was important to me that the film portrayed nature in all its beauty, but that those landscapes also had to be a little unforgiving towards Paulo, making him feel more isolated, alone and grieving, forcing him to find comfort in others. Another thing that I really wanted to do was to work with our sound person, Kirbie Seis. I had approached her and said, “I want to make a really quiet film and I need it to sound like the earth is grieving, but also make it sound like Iceland.” I’d often look around and see her off in the fields or by the side of the road with her microphone just recording sounds. So when we got back she had this library of sounds of Iceland, and every sound was incorporated into the design, and then Darren Morze came in with this emotional score that incorporated that and just leveled it all up. It made me so happy, it really was beautiful to sit and watch the film and hear. I could isolate all the locations from the recordings and it transported me right back. It’s very subtle and really what I was hoping we could accomplish. To make a very quiet film that felt like the Earth was crying out in grief.

I’m going to admit something: scouting was all done via Google Earth and Airbnb. I picked a few areas that I had been to and knew what to expect visually. It doesn't sound very glamorous, but we also did not have a budget that allowed us many options. We really lucked out though. We only have 3 locations, and once we found a place where we were going to live, all those locations were within minutes away just by pure luck.

Your film’s aesthetic brought to mind projects like Richard Linklater’s Boyhood and Eric Rohmer’s Le Rayon Vert that retain equal parts spaciousness and intimate psychological profiling. What filmmakers and movements inspire your work?

I have my favorite filmmakers that have inspired me to be a filmmaker, but I’m not sure how much each one inspired this film specifically. I suppose on some conscious or unconscious level it’s all in there. I do know for this film I had a small list of films I asked the crew and Hugo de Sousa the lead actor to watch. I wanted them to get a better understanding of the tone and pacing. Starting with Kieslowski’s Blue, and then Kelly Reichardt’s Wendy and Lucy, and finally Kogonada’s film Columbus. All three really set the tone for me and were a great starting point for inspiration. I’m guilty of being a fan of the “slow burn” movement of filmmaking. I don’t like that description as much. I like saying “the quiet film” movement!

This film seems to question the meaning and interpretations of family. We see Paulo drift from one companion(s) to the next, even winding up next to a mother and her child, as if he himself is the father. How does family and its significance vary from character to character? How does this film contribute to the redefinition of concepts we take for granted?

Yes and no. These characters represent the stages of grief one goes through, but I made a conscious decision to make them all female for a reason. That being that each woman he encounters are these representations of his mom. Who she was and who she became and these manifestations of her in various stages are what he is processing, accumulating to this final acceptance stage with the mother and child. It really depends on the audience and how they feel and experience it. I wanted to give options actually because I wanted the space there for people to feel they could make that decision of how they feel about it all on their own. Really that is what I hope for, that people walk away with one feeling and then have a slow-think, and a couple of days later it hits them with a different feeling.

What is on the horizon? How do you think Everything in the End will influence your next project?

The frustration of having a film that has gone through festivals this last year has been that most have been virtual. A festival allows a filmmaker to connect, especially emerging filmmakers. This being my first feature, it’s been a bit of a challenge to connect. Virtual hasn't allowed me many opportunities to meet and connect with future film collaborators, so in a way the next project feels like it will be starting from square one again. So the horizon looks a little murky right now. It for sure involves another film with a small crew in an intimate setting again and obviously a slow, quiet burn. So if that type of film peaks someone’s interest they should reach out!

Director: Mylissa Fitzsimmons

Running Time: 75 minutes

Trailer available Here

Premiering at the Bushwick Film Festival Oct 20-24 at watch.bushwickfilmfestival.com

Common Language: Lingua Franca and Auteurship

Isabel Sandoval is an auteur “staking her claim” in cinema. Sandoval’s control over her work is an important ownership, and in the film Lingua Franca, supports the film's themes of trans identity, addiction and immigration.

Written by Lex Young

Photo Credit via Lingua Franca trailer on Youtube

Isabel Sandoval is an auteur who has been creating her own home in cinema. Lingua Franca, which she wrote, directed, edited, starred in and produced, is a film where this control supports its trans identity and immigration themes. Each character is in conversation with their autonomy, home, and family. The control Sandoval exhibits over the film and its narrative is empowering, solidifying her importance in modern cinema and the vital need for trans folks and immigrants to have authorship over their narrative in cinema and life.

In Lingua Franca, each character grapples with control. The film begins with Olga, an elderly Russian immigrant who struggles with her memory. We see her in a kitchen, reminiscent of Akerman’s Jeanne Dielman, women who meander through routine, domestic ritual, finding comfort in this routine, but not happiness, a forced expectation of femininity. Odes to Akerman can be seen throughout the lonely landscapes of New York beautifully captured by Sandoval. This is a marker of Akerman’s cinema as well, emphasizing a separation between self, identity and place. Two women who are looking for themselves in a vast and crowded city, a struggle to find home.

The character of Olivia, played by Sandoval herself, is bound in constraints of care, a duty to her family, her job as a caretaker for Olga, and someone she paid to marry her for a green card. Throughout the film, she speaks with a faceless mother, whose voice we only hear through the phone, and she is seen preparing care packages for her family back in the Philippines. This faceless mother is a striking absence of an image, just a distant voice, emphasizing the separation between two homes and family.

Insecurity can be found in the character of Alex, the grandson of Olga, his own identity wrought with the instabilities of addiction and toxic masculinity. This is shown by Sandoval, through the character of Olivia, displays Alex and his toxicities with an empathy that comes from desire. Sandoval plays with this idea of a savior. Alex is someone who desired Olivia without knowing her fears of deportation, her status as an immigrant, her loss of a green card marriage, and her trans identity. When he does find out it’s through deception and influence from his friends who spew transmisogynist slurs. Sandoval beautifully depicts the ongoing and never ending fight with policy, violence and fear that plague immigrants and trans folk alike.

Lingua Franca ends with Olivia’s rejection of Alex’s marriage proposal, and Olga once again struggling to remember herself and routine. It’s an open ending, not exactly a conclusion but a cycle; we’re empowered all the same with the knowledge of Olivia’s choice of a new beginning. Olivia speaks on the phone to her mother of another job and that she met someone new. Yet we’re left alone with Olga, in her bleak kitchen, wondering about our place in the world. It’s a nod to the continuous journey of finding comfort in one’s own identity, and the continuous struggles of trans folks and immigrants.

Isabel Sandoval highlights the importance of trans folk and immigrants controlling one’s narrative. Her auteurship is vital in her work, and to the empowerment of trans and immigrant voices, a pedestal formed with her own hands.

Lingua Franca

Director: Isabel Sandoval

Year: 2019

Streaming on Netflix

Lex Young is currently watching movies, writing and making things in New York. Catch more of their work on Instagram

Arts and Education: 16k and Margo & Perry

Symone Baptiste, director of “Sixteen Thousand Dollars” and Becca Roth, director of “Margo & Perry” go in depth on using episodic form and comedy as tools for truth and change.

Written by Lex Young

“Sixteen Thousand Dollars” directed by Symone Baptiste and “Margo & Perry” directed by Becca Roth each use different tools of artistry and storytelling to highlight the importance of the medium of film as a method for education and awareness, not just entertainment. Their growth as projects are a testament to their success and the importance of their work and messages.

Photo credit via “Sixteen Thousand Dollars” Trailer

Baptiste is a stand-up show producer and booker in LA who was a showrunner for season one of “Call & Response” and has interviewed and directed talent for NBC. “Sixteen Thousand Dollars” is an episodic short film that won Best Narrative Short at the 2020 Bushwick Film Fest. The short explores ideas of reparations through a struggling college grad who tries to figure out how to spend his reparation check received in the mail. A writer and director whose personal mission is to foster diversity in the comedy space, Baptiste challenges viewers to see slavery reparations in a brand new light.

“It was absolutely principal that we added nuance to the debate on reparations, bringing the tough conversations around the subject to the forefront and facing them head-on.” In “Sixteen Thousand Dollars''

Photo credit via “Sixteen Thousand Dollars” Trailer

She uses comedy to explore these nuances. “It became extremely apparent that addressing the matter through comedy was the right move; it lowered the barriers to understanding the complex subject and gave it an edge.” The film has been shown not just in festivals but to college students, believing that the short form, as well as the comedic approach, are valuable for education and entertainment. “It’s a testament to the validity and truth behind the story of Sixteen Thousand Dollars”. The short has also been shown at Slamdance in it’s episodic category. After making “Sixteen Thousand Dollars”, Baptiste was approached several times about turning it into an episodic show. She praises the writing of Brodie Reed and Ellington Wells, who also star in the short. “The sibling dynamic they created on the page is impeccable. People want to see more of that, and I don’t disagree.”

Photo Credit: Director Becca Roth

Becca Roth is a narrative and documentary filmmaker who tells stories that explore themes of queerness and identity. Roth describes filmmaking as an important personal tool for self-expression, and her main character, Margo, uses her artmaking similarly. “For me, filmmaking has always been very, very personal. I wrote my first film when I was a teenager as a way to cope with my feelings for a female classmate that I couldn’t talk to anyone about.” Margo is an artist who interprets her world and identity through drawings and cartoons. “Through her relationship with Perry and her growth journey as an individual, her art becomes less self-deprecating and more expansive, imaginative, and inclusive.”

“Margo & Perry,” a proof-of-concept short, is the story of a young woman who babysits for a girl she believes to be the baby she gave up for adoption as a teen. Roth has written and directed multiple projects, including the 2017 short “Lens'' featured in the 2017 run of Bushwick Film Festival. The feature screenplay of “Margo & Perry” is one of ten screenplays selected by the Black List and GLAAD for the GLAAD list.

Photo credit via “Margo & Perry” Trailer

The short “Margo & Perry” was created from the award-winning feature screenplay. “I had to take the more complete story of the feature and distill part of it into a shorter piece that still demonstrates the characters and themes of the feature while being able to exist on its own as a standalone film.” She explains the importance of Margo's identity in both the short and feature. “Margo is also a queer protagonist, which is featured more overly in the feature version of this story, but I made sure to make it subtly clear in the short as well, and that is done through her art.”

Both films utilize different techniques of artistry and storytelling to explore themes of identity and reparations, and their growth and success prove the importance of film as a method of education and expression. Baptiste and her team are moving forward with pitching “Sixteen Thousand Dollars” as a series. “We’ve put so much hard work into developing a post-reparations world for nearly a year, so it’s been a long time coming.” The feature narrative film of “Margo & Perry” is currently in development and will be Roth’s debut feature film.

2020

Director: Symone Baptiste

Starring: Brodie Reed, Ellington Wells, and David Gborie

~

2020

Director: Becca Roth

Starring: Sofia Black D’Elia, Annie Parisse and Charlotte Macleod

Lex Young is currently watching movies, writing and making things in New York. Catch more of their work on Instagram

Filmmaker Tess Harrison: From Inspired Shorts to Her Feature Debut, The Light Upstate

Bushwick Film Festival alumna Tess Harrison discusses her short film work and her upcoming feature debut.

Written by Marisa Bianco

Photo Credit by filmmaker Tess Harrison

“I think I am terrified of losing someone - so finding a way to visualize that space in between life and death is comforting to me,” says Bushwick Film Festival alumna Tess Harrison about her upcoming film, The Light Upstate, which explores grief and its myriad of complexities. Harrison is a filmmaker and actor whose momentum is on the rise. Her work in short narrative film and music videos shows her capacity to tell visually and narratively exciting stories in just a few short minutes. Soon we’ll have the opportunity to see what Harrison can do with the feature-length format in her directorial debut, The Light Upstate, an adaptation of her 2018 short Take Me Out with the Stars, an official selection of the 11th Annual Bushwick Film Festival.

Across Harrison’s directorial work is a talent for capturing setting and character in harmony. The worlds in which her films take place feel real, and the characters feel as if they are in and of those worlds. In her first short, 2015’s DOG, a group of teenagers sit around a bonfire, playing truth or dare. The conversation is silly and innocent enough until one character, Alex, admits a dark secret. It's a startling change in the tone of the conversation, but it works because the film’s visual style remains constant. In the beginning, the smiles and laughter of the bantering teens don’t match the ominous shadows of the flames moving across their faces. It is almost a relief when Alex tells his secret—it diffuses this tension, the mismatch between visuals and dialogue, that Harrison so expertly builds. We’re left with the melancholy of watching these teens’ relationships change before our eyes. The camera lingers on one girl, who is realizing, perhaps for the first time, that we don’t always know people as well as we think we do.

Harrison returns to the bonfire setting from DOG in her 2018 short Take Me Out with the Stars. The short follows two adult siblings as they struggle with the fact that their dying father fled the hospital he was staying in. In the end, the siblings sit at a bonfire, looking up at a stop-motion animated yellow star, representing their father’s spirit, that somehow they can both see. Harrison reveals that she “wanted the star to feel like it was in between the world of the film and the world of the audience.” She says that “the movement of [animator Zuzu Snyder’s] figures really spoke to me,” and “stop motion in particular has such a material presence on screen, especially against a live-action background.” Harrison uses the star to shift focus, which she suggests “allows for the audience to feel that sense of dizziness that you experience in grief - that sense that the world is moving under your feet.”

Take Me Out with the Stars is the type of short that tells a complete narrative, yet draws you into its world so skillfully that I couldn’t help but yearn to know more about the characters and their relationships—with each other and with their father. I want to live in the magical realism a little longer, where we can see the love and the spirits of those we grieve animated across our skies.

Photo Credit by filmmaker Tess Harrison

In The Light Upstate, the siblings are portrayed by Harrison and her real-life brother, Will. Harrison wrote the film for herself and her brother, and “though we are definitely not the characters in the film, we share a shorthand as actors and siblings that created an inimitable tension on screen.” Tess and Will Harrison previously acted together in Tess’s 2015 award-winning short It’s Perfect Here. Describing their experience making the feature, she says, “It was super challenging and rewarding to work on this material together, so hopefully that creates a unique experience for an audience.” In the feature, the missing parent is instead the mother, “a renowned children’s book author and illustrator.” The literal connection to childhood in this character allows the film’s tone to be “steeped in this childlike, magical imagery.” Tess’s character, Eve, “is burying herself in her mother’s art as a way of accessing and staying in the magic of her childhood, while the reality of her mother’s death is pressing on her.” Harrison focuses on the character’s “minute changes,” expressing her hope that “those little shifts in self-awareness are as moving for an audience as they are for me as the writer, director and actress.”

Harrison also has an impeccable sense of how to use music and sound design in visual storytelling. In Take Me Out with the Stars, the titular animated star skips across the screen, seemingly enlivened by the spritely score. The yellow star and its music provide a warm balance to the cool winter tones and the characters’ dark grief. Standout sound design is further apparent in her 2017 short film Things Break In, an official selection of the 10th Annual Bushwick Film Festival. At certain moments we hear the gentle, folksy score, punctuated by short swells of strings and piano, while at other moments we hear the sounds of the farm and nature, whose musical cadence seems like an extension of the score. Then, when a thunderstorm comes, nature and score come together like a serendipitous symphony, just as the two characters come together.

Photo Credit by filmmaker Tess Harrison

In addition to her short film work, Harrison co-directed a narrative podcast series produced by and starring Cole Sprouse called Borrasca in 2020. Written by Rebecca Klingel, whose credits include The Haunting of Hill House and The Haunting of Bly Manor, Borrasca is a horror story and mystery reminiscent of Stephen King’s It and Nic Pizzolattos’ True Detective. The congruity of dialogue, sound effects, and music makes this story an immersive auditory experience. Harrison describes directing a podcast as “like theatre in a lot of ways. Moves fast, you can play around with the performances and clock the tiniest changes in delivery when you are only working with the voice.”

What’s next for this emerging writer, director, and actor? This fall, Harrison will participate in the Nostos Screenwriting Retreat in Italy, where she’ll work on the film The French Movie, “about an American teenager studying abroad in the south of France in 2005,” which explores “themes of sexuality, coming of age and national identity.” She is also working on an adaptation of her short film, Things Break In. You can see all of Tess Harrison’s work on her website.