The Last Out: Q&A with Directors Sami Khan and Michael Gassert

Written by Aubrey Benmark

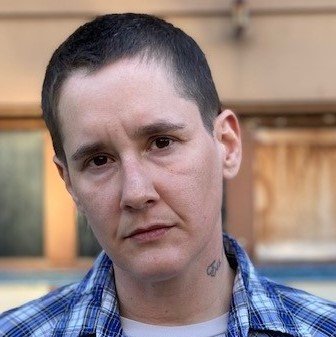

Carlos González in The Last Out Photo Credit: Sami Khan and Michael Gassert

October means one thing to die-hard baseball fans— Major League Baseball playoff season. Millions across the nation collectively hold their breath at every pitch as the best teams battle their way towards the World Series, but for Cuban athletes it takes significantly more than talent and training to bring them to the pinnacle of their profession. Due to a decades long trade embargo between the U.S. and Cuba, most Cuban ballplayers must face perilous travel conditions via human smugglers as they defect from their country knowing they might never see their families again, risking exile if they succeed, and all before they reach a foreign training camp where they are required to obtain residency, or no MLB club can even consider them.

The Last Out, a feature-length documentary directed by Oscar nominated Sami Khan and Michael Gassert, details the journey of three players, Happy Oliveros, Carlos González, and Victor Baró, as they struggle to make their greatest dreams a reality. Filmed over a four-year time span, Khan and Gassert dedicated themselves to an honest and emotional depiction of the nefarious Cuban pro baseball pipeline. At times the story is heavyhearted, the disappointment and homesickness from Oliveros, González, and Baró is palpable, but the camaraderie and love they offer each other uplifts the soul. Despite devastating setbacks, the men forge ahead to build better lives for themselves and their families. I’m fortunate to ask the directors of The Last Out, Sami Khan and Michael Gassert, a few questions about the inspiration behind this story and the process of making it.

As baseball fans yourselves, why was it important to you to capture this particular story, and did you know it would resonate with a much wider audience?

Sami Khan: Early on in the pandemic, there was nearly a collective “eureka!” moment for Western civilization. We briefly got a window into all the invisible people our fragile economy depends upon. Not just the nurses and doctors but the janitors, the truck drivers, the grocery store employees, the farm workers, and factory workers - they’re all threaded together in this delicate tapestry that modern life depends upon. In March 2020 when things screeched to a halt, we got a glimpse at that tapestry. Sadly, that moment has since been lost and we’ve moved on with our absurd existence of abundance and convenience. But, for us, about seven years ago, we started to think about that secret tapestry in baseball, specifically around the wave of dangerous defections from Cuba and the hidden cost, financially and morally, of the national pastime.

Michael Gassert: When Sami first pitched me this idea I immediately felt that dream you have as a little kid to reach the major leagues and come through for your team in the biggest moments. Any kid who’s thrown or hit a ball has also chanted; bottom of the 9th, two outs, bases loaded… But more than just chasing a dream with prospects in real time, I knew that Sami had keyed into something much bigger. That the inequities created by the US trade embargo on Cuba could lead us to some dark places as the demand for Cuban ballplayers was at an all time high. We soon discovered that by telling that story in a very intimate, personal way, we can open a portal to some bigger questions about immigration, the commodification of athletes of color, and the cost of the American Dream.

The migrant trail into the U.S. is often associated with manual laborers, not professional athletes, and yet the audience is afforded an up-close view of Happy Oliveros’s passage after he is surreptitiously cut from the training camp in Costa Rica. Was there a point in the journey when you feared that Oliveros wouldn’t make it into the United States?

MG: Happy’s journey and the process of making this documentary overlap in many areas but perhaps most comprehensively in their inherent uncertainty. There have been many twists and turns along the way, some foreseeable and others not. But like Happy, I think we always just tried to put ourselves in position to be successful and never give up. Palante siempre, candela!

There were certain moments along the way where Happy’s original plan didn't pan out and the odds were against him, but he found a way. For example, in a moment that you don't see in the film at the first border crossing into Nicaragua, Chele and I saw Happy being escorted by a border agent back into Nicaragua after we originally split off. I thought we might not reunite for a long while. But Happy met us on the other side with a 30 day visa no less.

But as the situation in Costa Rica worsened and the political situation changed under our feet, our concern grew for all the guys and all immigrants, in fact, who face such precarious circumstances. When Carlos tried to cross into Nicaragua a few weeks later, he had a much harder time, was stripped of all his money, and was fortunate to make it back to San José in one piece to try again the following month.

Official Movie Poster The Last Out

The inclusion of the athletes’ families back home in Cuba was especially touching to see in the film, as all of the men made enormous sacrifices with the intentions of supporting their loved ones. How was it for you to spend time with the families, knowing their sons could not go home and do the same?

MG: This was perhaps one of the most touching experiences for us as filmmakers. You feel so much for these guys not being able to just turn around and visit their families whom they love so much while they’re out there risking everything for them. Sami and I went on an epic adventure not just to meet up with a few relatives but track down and spend meaningful time with the immediate family members of all the guys, even those you don't see featured in the story. We felt it was vital in telling their story to have a strong, first hand sense of what they mean to their loved ones. Spending time in the players’ houses, eating their favorite meals cooked by mom all brought us closer to them and how meaningful of a sacrifice they each made. There were pig roasts in Mayari, river bathing in Baracoa, stories of achievement and longing everywhere we went. Being able to bring those photos, videos, personal notes and first hand accounts to the guys meant so much to them but also deepened the trust we had built. It also made more clear to them what we were really after in following their stories. I remember walking back to the barber shop with Baró after the emotional moment when he watches the video message from his mom at the stadium and he just turns to me and says, “I get it now Mike. I get it mi hermano.”

Near the beginning, your film highlights a troublesome statistic, “In the last five years hundreds of baseball players have left Cuba. Only six have made it to the Majors.” Initially over two dozen eager baseball scouts visited the training camp to assess Oliveros, González, Baró, and the other players’ skills, only for their contract negotiations to dwindle after months of not being able to obtain Costa Rican residency. While the odds of making it into any professional sports league are staggering, in your opinion how much of the austerity of their situation affected the players’ performance on the field as time wore on?

SK: We definitely saw the toll wear on the guys. One of the hardest things for all of them was seeing guys they used to play against sign multi-million dollar deals while they were waiting for their paperwork to clear. I vividly remember one instance where Mike and I rushed to tell the guys that one Cuban player they knew had just signed a huge contract and Happy said something like “That’s good for us. We’re at that same level.” But the contracts never came. A large part of that was because of mistakes Gus and his team made in the paperwork, another huge part was that the market shifted against the guys, and the final part was the emotional and physical toll it took on the guys which led to declining performance. But can you really fault someone for having one bad showcase when they’ve risked everything, left their homeland and their family and aren’t sure if they can trust the process anymore?

In previous interviews, you’ve discussed the cost that making it to the pros exacts upon the players, and that we are living in a time where athletes are heeding the call to social justice. As a devoted baseball fan myself, is there anything that fans can do, beyond raising their awareness of such issues, in order to support the current and future Cuban ballplayers trying to make it to the U.S.?

SK: In all honesty, fans should start to develop a sense of outrage that extends beyond just whining over a slugger popping pills or a team stealing signs. There are very shady things that go on in professional sports where young athletes are exploited by the system and too often fans have the attitude: “Oh, well if my team wins, I don’t really care.” That’s a messed up way to live your life.

One concrete thing right now fans can do is support Minor League players who are fighting for a living wage. There are ballplayers, Cuban, Dominican, and American who are making starvation wages in the Minors. Organize your buddies to write emails to your team’s leadership to ask that they pay their Minor Leaguers humanely. That would be a good start.

Directors: Sami Khan & Michael Gassert

Running Time: 84 minutes

Available to view Oct 20-24 at watch.bushwickfilmfestival.com